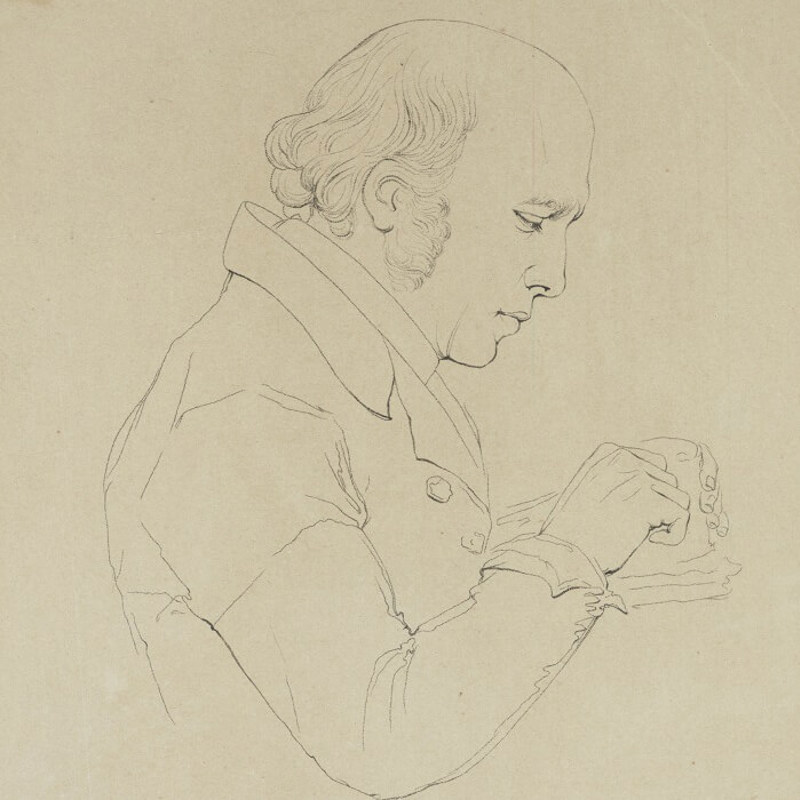

Benedetto Pistrucci

The association of Benedetto Pistrucci with the Royal Mint began soon after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Arguably the most mercurial and temperamental engraver ever to work at the Royal Mint, Pistrucci had been born in Rome in 1783 and had established for himself a considerable reputation as a gem engraver. He had been in France during the final days of Napoleon’s regime and it may well be that William Wellesley Pole, the Master of the Royal Mint, was among those who tempted him to come to England.

First coins

Pistrucci was quickly commissioned to provide portrait models of George III for the new gold and silver coins planned for issue in 1817. At first he was unable to engrave these models directly into steel, a task that had to be entrusted to the Royal Mint’s own engravers. But he was unhappy with the result and mastered the technique for himself, so that when he produced his classic St George and the dragon for the new sovereigns of 1817 the design was entirely his own. Still used today, Pistrucci’s St George has enjoyed remarkable longevity and has ensured the survival of his name and reputation. Perhaps, indeed, it is appreciated more now than in 1817, though when its use was extended in 1818 to the new crown piece it produced a coin that a shrewd contemporary judge described as ‘the handsomest coin in Europe’.

Later coins and medals

As a foreigner Pistrucci could not be appointed Chief Engraver, much as he wished for the post and for the financial security of a good salary. Nevertheless, he continued to be employed by the Royal Mint in a lesser capacity and in 1820 he engraved a skilful, if somewhat unflattering, portrait for the first coins of George IV. This was followed by the official Coronation medals of 1821 but shortly afterwards he declined to copy a bust of the king by the sculptor Francis Chantrey. Such high-handed behaviour effectively brought to an end his contribution to the coinage, but he remained involved on occasion with medals and in 1828 the post of Chief Medallist was specially created for him. His official medallic output, however, was meagre and the portrait of the young Queen Victoria on her Coronation medals of 1838 was certainly not to everyone’s taste.

Waterloo Medal

The problem with Pistrucci was not just his fiery temperament and his bitterness at not being appointed Chief Engraver when, as he insisted, the post had been promised to him by William Wellesley Pole. There was also the long-standing difficulty caused by a large commemorative medal for the Battle of Waterloo, officially commissioned from Pistrucci for presentation to, among others, the allied sovereigns who had been victorious in defeating Napoleon. Pistrucci had conceived the medal on the grandest scale and his progress was slow – and deliberately so since he feared that, having put himself beyond the pale by his obstinate behaviour, the Royal Mint would sever its association with him as soon as he handed over the dies.

Completion of the dies

The work dragged on and, having invested so much money in the ‘coming wonder’, successive Masters of the Mint felt obliged to encourage the argumentative and dilatory Pistrucci to complete the dies. Years passed and eventually, in 1849, Pistrucci was able to hand over the completed dies. These unfortunately were so large that they could not be hardened and the outcome of a project that had begun 30 years before was that no medals could be struck. The dies survive and undoubtedly represent a triumph of medallic art and a masterpiece of engraving skill.

With their completion Pistrucci’s association with the Royal Mint finally came to an end and he died at Englefield Green, near Windsor, in 1855.

You might also like

William Wyon

Wyon's enduring reputation rests largely on his coin and medal portraits of Queen Victoria.

William Wellesley Pole, Master of the Royal Mint 1814-1823

Pole was a man of energy, ability and influence.

Half-crown

Like the crown, the half-crown was introduced as a gold coin during the reign of Henry VIII.