Thomas Simon collection

There have been many supremely talented engravers and designers associated with the Royal Mint over its long history. Some of those engravers, such as Benedetto Pistrucci and William Wyon, are still highly regarded; in Pistrucci’s case, his design of St George and the dragon still graces the sovereign on a nearly annual basis. But there are less well-known, often overlooked figures, who deserve equal praise for their work. One of those is the former Chief Engraver Thomas Simon. Born in 1618, Simon grew up in a turbulent world, one that witnessed the horrors of the English Civil War, the rule of England’s only republic and the restoration of the monarchy. Although it was an era of change, it was a period which also presented opportunities to men like Simon who were able to ride out the political storms of the day and find in that turbulence a place for their art.

Explore more about the life and work of Thomas Simon in our curated collection.

As an artist, Simon began his career apprenticed to the Goldsmith George Crompton in August 1633. For reasons now lost to us this apprenticeship did not work out and just two years later he changed master, working under the tutelage of Royal Mint Chief Engraver Edward Greene. It may well be that Simon displayed an aptitude for engraving that better suited him to working on coinage and medal dies but, whatever the motivation for the change might have been, he clearly took to his new subject matter. Within a year of working under Greene’s guidance he was taking on high profile work, engraving a seal for the Admiralty, which was soon to be followed by another seal for the Earl of Northumberland in 1638.

Greene died in 1644, and a year later Simon was appointed joint Chief Engraver with Edward Wade, sharing a salary of £30 a year. This appointment came at a time of great turmoil, the country being embroiled in war as the King and Parliament fought each other for supremacy. Simon firmly sided with the Parliamentarians, remaining at the Tower of London to continue his work, and whilst he initially had to share the post, he was rewarded for his service by being granted the sole position of Chief Engraver at the end of the conflict. The new Commonwealth presented numerous opportunities for Simon, and his talent ultimately caught the eye of the Parliamentarian General, and later Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, who was so impressed that he made him his personal medallist.

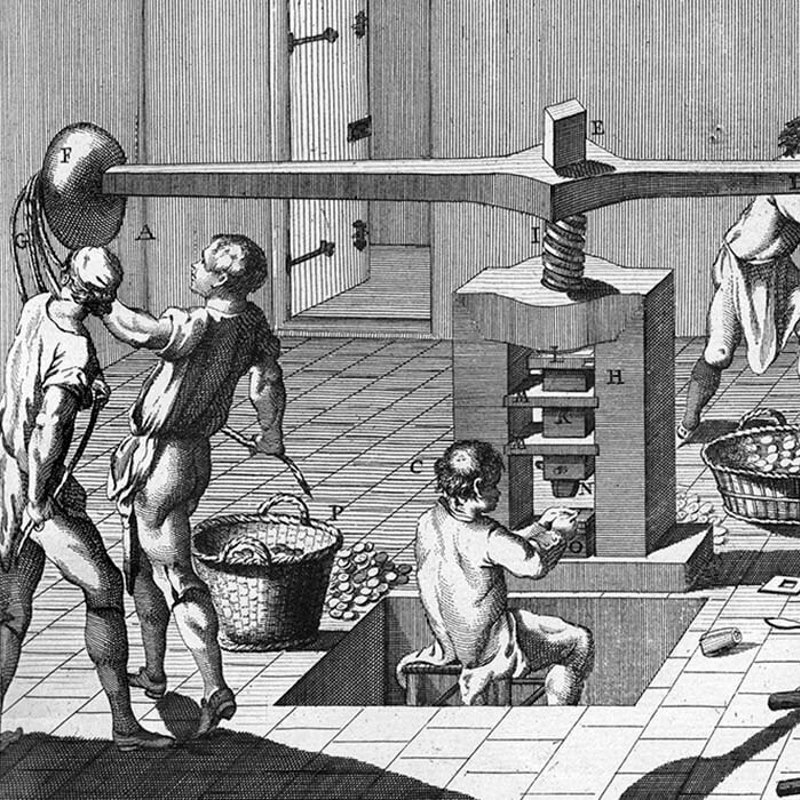

His close association with the Commonwealth and Cromwell did not endear him in the eyes of the Charles II. With the return of monarchy in 1660, Simon lost his position as Chief Engraver to Thomas Rawlins, who had remained loyal to Charles I, and found himself in the difficult position of having to plead to the king for his job. Successfully returned to the post by June 1661, he engraved the tooling for the first hammered coins of the reign, but the winds of change were blowing through the Royal Mint. Soon after the start of 1662 a Flanders family of engravers, John, Joseph and Philip Roettier, were summoned to England and ordered to prepare designs for a new coinage to be struck on machinery installed by the French engineer Pierre Blondeau. From that point on it would be the Roettiers that dominated the production of coinage dies and, despite his best efforts, Simon would be confined to a minor role engraving dies for Maundy pieces right up until his death during the Great Plague of 1665.