The Making of the Great Seal

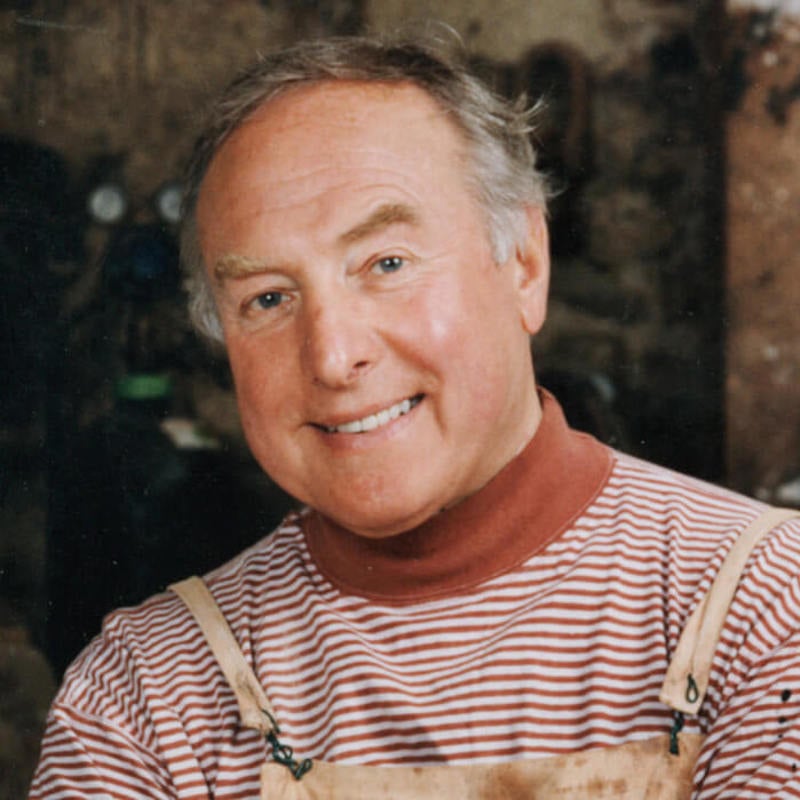

By James Butler

When I was invited with a small group of distinguished artists to submit designs for a new Great Seal of the Realm at the beginning of 2000, my first reaction was to refuse. I was working on a large figure for the Fleet Air Arm memorial and was hardly in the mood to work on a relief sculpture of Her Majesty, twelve inches in diameter. Having reflected on the offer, however, I decided to visit the Mint to have a look at how artists had approached designing Great Seals down the centuries. In the series of seals that I was shown dating back hundreds of years what struck me, and especially so in the earlier seals, was the power of the simple image of the monarch and how attention naturally focused on the individual.When I returned home and began working on the designs I wanted to capture something of this medieval simplicity and power. I worked on a number of swiftly drawn sketches, for which I was to be paid, and submitted them without any serious thought that I would be successful.

Cutting the obverse design into a block of silver

When at the beginning of April Graham Dyer, Secretary to the Royal Mint Advisory Committee on the Design of Coins, Medals, Seals and Decorations, phoned me to tell me that I had won the competition, my feelings were mixed. It was indeed a great honour to be chosen but I had little confidence in my ability to work on the small scale that would be required. My drawings had a rapid fluidity and now I had to translate them into solid form. The design brief for the Great Seal was very limited in subject matter. There were three options: the Queen seated, facing outwards; the Queen on horseback, facing to the left and finally the Royal Arms. The Advisory Committee preferred my designs of the Queen seated for the obverse and the Royal Arms for the reverse. I began modelling in plasticine on a twelve-inch diameter relief but I found this extremely irksome since I do not like the feel of plasticine and modelling on such a small scale was very inhibiting. Nevertheless, I persevered and submitted two models to the Mint for presentation to the Committee.

In the rich wood-panelled setting of Cutlers’ Hall in the City of London on 6 July the Advisory Committee deliberated over my unfinished models. While members gathered their thoughts I was in another room, waiting to be called in to confront this august body of a dozen or so men and women. As I walked into the room I was immediately reassured because I recognised one or two familiar faces and indeed it proved to be a very constructive meeting.

The Committee rightly felt that some of the spirit of my original drawings had been lost in the plasticine models. I quite agreed with them. One of my most recent sculptural commissions had been a ten-foot-tall statue of Daedalus with a fifteen-foot wing-span, and having worked at such a scale for many years I now found it difficult to translate my vigorous style to the confines of the low relief that was required in this instance. But at the same time I had come so far with this project that I did not want to give up now.

The Committee, to their credit, came to my rescue. Members still had faith in the drawings that I had originally submitted and they felt sure that I could create an excellent new Great Seal if only I could capture something of that spirit. ‘How large would you like to work?’ I was asked. ‘About this wide!’ I said, spreading my arms. ‘All right!’ I was told. ‘You can model both sides in clay at twenty-eight inches in diameter.’ I now had the freedom to work at a size with which I would feel more comfortable and I left Cutlers’ Hall that afternoon a good deal more relieved and with renewed enthusiasm.

Over the next few weeks I continued to work on both sides of the seal, on the seated portrait of the Queen for the obverse and on the Royal Arms for the reverse. As word spread through official circles that a new seal was being prepared the chance of a sitting with the Queen began to emerge, and on 11 October she graciously allowed me to attend at Buckingham Palace. She kindly wore the type of long dress and cloak that I had chosen for my design and while there I spent half an hour taking as many photographs as I could. Never having been to Buckingham Palace before, and being allowed such freedom of access to the Queen, this sitting was a special honour and was invaluable in completing the portrait.

Another Advisory Committee meeting was scheduled for 2 November, a meeting that would determine whether my large clay models for the new Great Seal would be accepted or rejected. I was again invited to Cutlers’ Hall and was this time confronted by a Committee much more favourably disposed to my work and after suggesting one or two amendments members recommended that work should now begin on actually generating the seals themselves. My clay designs having finally been accepted, I cast them into plaster and presented them to the Royal Mint, which in practical terms meant the models were now in the hands of Marcel Canioni, the Chief Engraver. The Royal Arms, which is the reverse of the Seal, was copied from my twenty-eight inch model to a twelve-inch plaster by the Engraving Department, who modelled the design with great skill and assisted me enormously by also cutting the lettering. The obverse, though, presented somewhat more of a challenge; since it was not possible for another engraver to copy the work at a smaller scale, a way had to be found to accommodate my large model on a modern scanning machine that was designed for work typically half the size. But thanks to the miracle of modern technology, a little bit of ingenuity and the great skill of Marcel Canioni and his colleagues, my work was reduced using a computer process from a twenty-eight inch plaster cast into a six-inch design cut back to front into a round block of silver.

Designing the Great Seal has been a wonderful experience for me not least because I have been introduced to many new processes of which I had no previous knowledge. I have also had the privilege to work with craftsmen at the Mint of enormous ability and understanding; the whole exercise has been a genuine team effort.

The final chapter in the making of the Great Seal was when my wife and I were invited by Lord Irvine, the Lord Chancellor, on 18 July 2001 to his private rooms in the House of Lords to celebrate the official beginning of the use of my design. On that day, at a meeting of the Privy Council at Buckingham Palace, the Queen ceremonially defaced the old seal, which had seen almost fifty years of service, with the light blow of a hammer, and the legislation before the Council was then passed under the new Great Seal. In the River Room, overlooking the Thames, and with several of the people present who had been material in working to this end, Lord Irvine displayed the new and the old Great Seals, and together we toasted a successful outcome. Lord Irvine spoke warmly about our achievement and indeed he was so taken with my original large models that they were placed on display in the House of Lords during the summer recess for the benefit of visitors to the Palace of Westminster. Before Lord Irvine concluded he presented me with an impression of the old Great Seal which had been designed by Gilbert Ledward RA, a very distinguished sculptor for whom I had worked after leaving art school. My connection with Ledward gave me a very personal reason to feel glad that I had been involved in this whole business but it was also very gratifying to be part of an interesting historical link in a great tradition.

You might also like

James Butler

A professional sculptor, James Butler MBE RA designed the 2004-dated 50p celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the first four-minute mile by Roger Bannister.

Conserving Wax Seals

Conservator Clare Rowson shares her experiences of a conservation internship at the Royal Mint Museum.

The Royal Mint Advisory Committee

The Committee was established in 1922 with the personal approval of George V.