Decimalisation

...this beautiful and venerable monetary complex

Anthony Burgess, You’ve Had Your Time (1990)

In the early 1960s Britain still used a currency system of twelve pennies to the shilling and twenty shillings to the pound. It was a system whose origins stretched back to Anglo-Saxon times and beyond, and which besides its enduring practical function of oiling the wheels of daily commerce had enriched the very language and literature of the nation. Tanners and bobs, ha’pennies and threepenny bits, were instantly recognisable descriptions, and the romance of the coinage was enhanced by the presence of coins of Queen Victoria, some of them 100 years old. Long familiarity had inevitably generated a deep-rooted affection: a beautiful and venerable currency, certainly; cherished, too; but undoubtedly baffling to those not born to its complexities.

These old accounts provide a reminder of the need to use three columns of figures for £sd calculations

...a momentous and historic decision

James Callaghan, House of Commons, 1 March 1966

On 1 March 1966 the Chancellor of the Exchequer, James Callaghan, announced that the centuries-old £sd system would be replaced by a decimal currency in which the pound was to be divided into 100 units.

It was a change that had been in prospect since the middle years of the 19th century, when the decimal lobby had been strong enough to secure the introduction of a coin valued at one-tenth of a pound. Other countries, once also wedded to £sd, had been less reluctant to shy away from the temporary disruption that a decimal coinage would bring and by 1966 there was a danger that Britain might soon be the only major country in the world without the benefit of decimal currency.

The decision to go decimal was seen and justified as an aspect of the wider modernisation of Britain. The greater simplicity of the decimal system would be an important aid to productivity, making money calculations quicker, easier and less liable to error, and benefiting machines as well as people. In schools significant time would be saved by not having to teach children the intricacies of £sd.

Recognising the enormity of a change that would affect every business and household in the country, that would wipe out the ingrained money habits of generations, the government proposed a five-year preparatory period before changing over in 1971.

Decimal pound starts storm

The Sun, 13 December 1966

Startling as it was, the Chancellor’s statement nevertheless found broad acceptance of the principle of decimalisation.

Where sharp controversy emerged was over the choice of system, with most retail associations and consumer groups favouring ten shillings and not the pound as the major unit. Such a system, it was argued, fitted in better with the existing coins, enabling the popular sixpence to be retained as a 5p piece and the half-crown as 25p, and seemed to offer greater protection against price rises.

On the other hand, leaving the pound intact avoided a disconcerting break in continuity by maintaining a familiar point of reference. It was also likely to be less disruptive to the business world, where a higher value unit was more appropriate for a well-developed industrial and trading economy.

The government’s decision in favour of the pound, though fiercely challenged, was confirmed by the Decimal Currency Act of 1967, which also specified that the minor units would be called new pence rather than foreign-sounding cents.

...to facilitate the transition from the existing currency

Decimal Currency Act, 1967

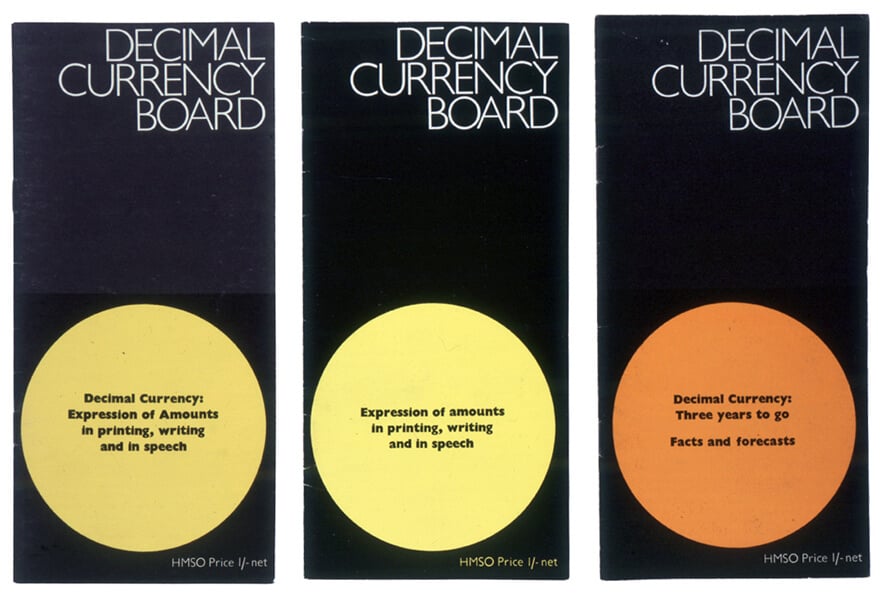

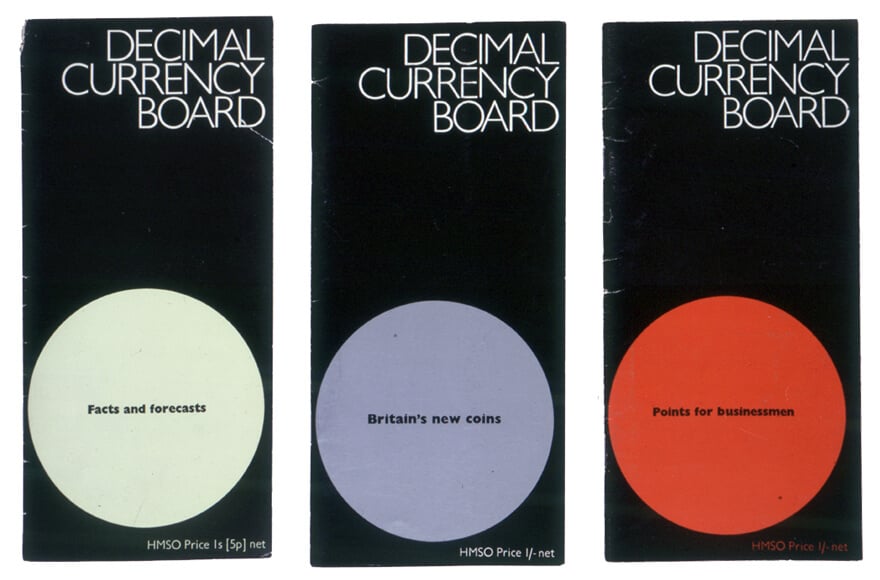

Established by the Act of 1967, the Decimal Currency Board was charged with overall supervision of the change-over.

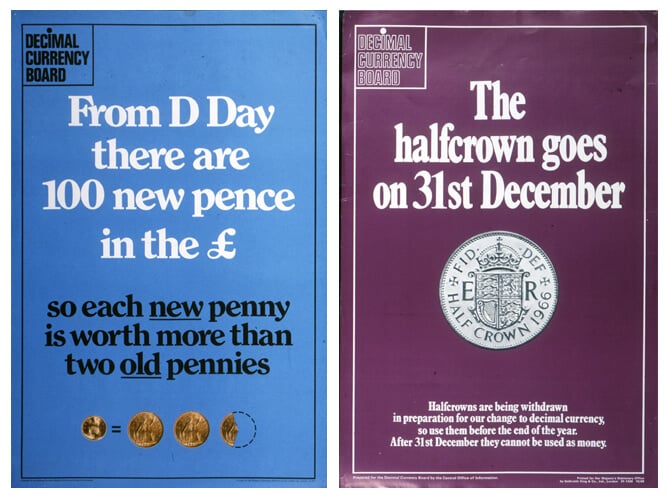

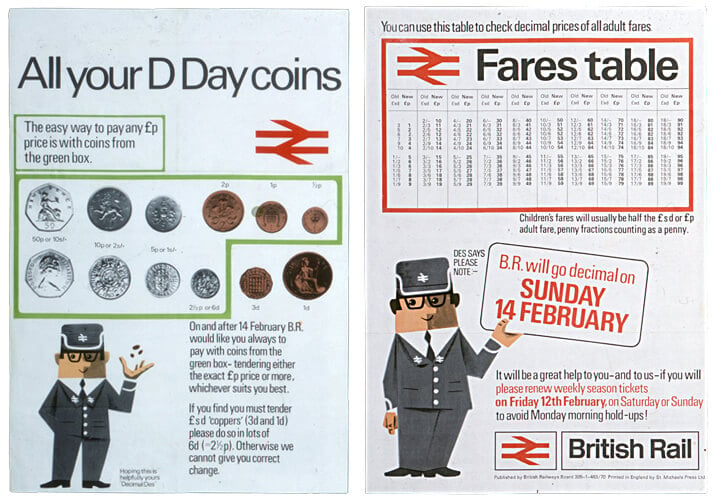

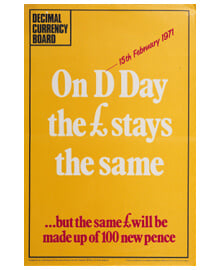

The strategy of the Board was to draw the sting from Decimal Day, soon to be firmly set for 15 February 1971. This it attempted to do not just by calming anxiety, particularly among older members of the community, but by reducing to a minimum the changes left until D Day itself. In other words, D Day was simply to become the culmination of a series of carefully planned changes.

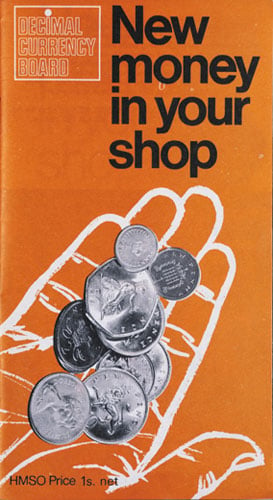

The Board’s duties included the provision of information, guidance and advice, and the promotion of arrangements for the adaptation or replacement of equipment. Its role was therefore largely advisory, rather than executive, stimulating others to take action and generally serving as an intermediary between government and the private sector.

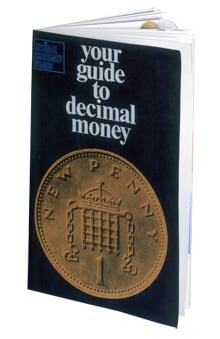

This required regular contact with all those bodies most directly concerned, such as the Royal Mint, the British Bankers’ Association and the Post Office, as well as a host of other associations and representative organisations. And it also involved the Board in advertising, in the publication of a regular Newsletter, in the preparation of millions of booklets, and in devising conversion tables that would be fair to both buyers and sellers.

Stressing the benefit of early and detailed planning, the Board first concentrated on business management, before switching its attention to retailers. It was only towards the end of the preparatory period that it deliberately targeted the general public, launching one of the most intensive publicity campaigns ever directed at the people of Britain.

...as clear and simple as possible

Royal Mint, design brief for decimal coins, November 1966

For most people the milestones between the announcement of 1966 and D Day in 1971 were marked by changes to the coinage – by the withdrawal of certain of the old £sd coins and the phased introduction of new decimal coins. Indeed, of the tasks that fell directly on the government, physically the most important was the production of the new coins by the Royal Mint.

Even to settle the dimensions of the decimal coins was not easy. Not only did the different denominations need to be readily distinguishable by sight and touch from each other but they also needed to avoid being confused with existing £sd coins. At the same time there was a desire to take advantage of the change by reducing the size and weight of the coinage so as to make it less troublesome to transport and less demanding of pockets and purses.

As for their designs, these had to an extent been anticipated and a new portrait of Her Late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II by Arnold Machin had already been prepared and approved with decimal coinage in mind.

For the reverses similar preparatory work was set aside in favour of a public competition, announced in November 1966. More than 80 artists took part and from the 900 or so designs that were received a series by Christopher Ironside was eventually approved. These, for the ½p, 1p, 2p, 5p and 10p pieces, were unveiled in February 1968 and drew praise for the lack of clutter that the design brief had urged on the artists.

Enter the 50p

Decimal Currency Board Newsletter, September 1969

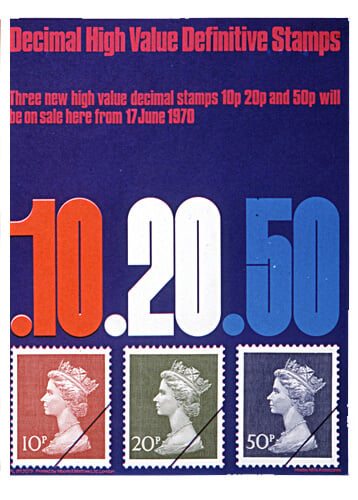

The first of the new coins, the 5p and 10p, began to be issued to the public in April 1968. Because they corresponded exactly in size and value, they were able to circulate alongside shillings and florins and served a useful purpose in preparing the public for what was to happen and in offering reassurance about the simplicity of the change-over, now less than three years away.

The unusual shape of the 50p was suggested by H. G. Conway, a member of the Decimal Currency Board. As originally designed, the coin showed an arrangement by Christopher Ironside of the Royal Arms

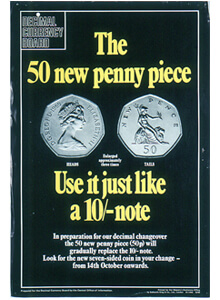

In October 1969 the 50p piece joined the 5p and 10p in circulation. If its design could be described as traditional, for coinage its equilateral curve heptagon shape was revolutionary, making it distinctive and giving it a constant breadth that allowed it to roll in vending machines. Yet despite having been the subject of more research and consultation than any previous coin in British history it was greeted with undisguised hostility.

Fortunately, the alarm, based in part on fear of confusion with the 10p, was short-lived and the coin quickly fulfilled its purpose of replacing the ten-shilling note, whose active life of only four or five months had made its production, circulation, withdrawal and destruction an increasingly expensive operation for the Bank of England.

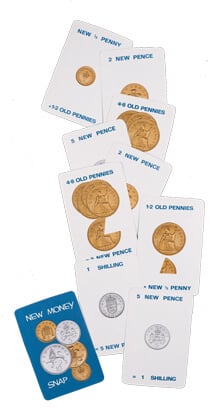

So, with the issue of the 5p, 10p and 50p, people were becoming thoroughly familiar long before D Day with the look and feel of three of the six decimal denominations. The remaining three coins, with no exact £sd equivalent, were not to be released until D Day itself but even here familiarity was promoted by the sale from June 1968 of large numbers of special souvenir sets of ½p, 1p, 2p, 5p and 10p pieces.

Save our sixpence

The withdrawal of the old £sd coins prompted a collecting mania which was directed not simply at the older coins in circulation. It also saw the speculative hoarding of bags of £sd coins in the hope that a perceived scarcity would increase their value, a difficulty that was countered by using the same date, 1967, on all new £sd coins struck before D Day.

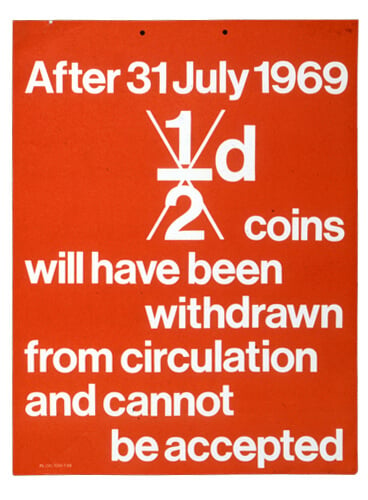

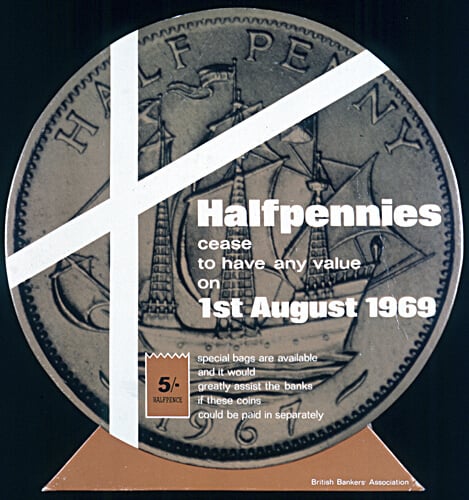

Two £sd denominations – the halfpenny and the half-crown – were withdrawn before D Day. There was no role that either could conceivably play after decimalisation and it was thought best to remove them entirely, especially as they clashed in size with 2p and 50p pieces. The halfpenny, nearing the end of its active life in any case, needed little assistance to disappear but the impending demise of the half-crown, because of its high value and its use in machines, was widely advertised by the Decimal Currency Board.

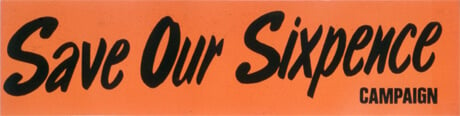

Both were relinquished by the public without a struggle, but not so the sixpence. The handy little tanner was a very popular coin and, though reason suggested that after D Day it would serve no practical purpose as a 2½p piece, a large and vocal section of the public could not accept the prospect of its removal.

In the first few months of 1969 and then again early in 1970 feelings ran remarkably high. Public opinion, indeed, proved so strong that, with the controversy threatening to disrupt all the careful preparations for D Day, the government conceded that the sixpence could survive for at least two years after decimalisation.

Set fair for D Day

Decimal Currency Board Newsletter, August 1970

By August 1970, with the future of the sixpence at least temporarily resolved, the Decimal Currency Board could claim that preparations for D Day were well on course.

Conversion of business machines and computers was largely complete or the subject of firm planning, while surveys of retailers showed that the vast majority had taken some steps to prepare for D Day. Similar surveys were revealing that even among the general public there was a healthy and increasing awareness of the change and, what was to be a vital factor in the success of the whole operation, no real hostility to the notion of decimalisation.

With a few months still to go, the Royal Mint had produced hundreds of millions of the new coins. The stockpile of decimal bronze coins was virtually finished, having been struck not at the existing Royal Mint in London but at a new Royal Mint at Llantrisant in South Wales opened by the Queen Elizabeth II in December 1968.

The problem had now become one of ensuring that these coins were in the right places at the right times and in the right numbers: that there might be local shortages of new coins on D Day was a disaster too awful to contemplate.

As well as this logistical headache, the Decimal Currency Board was just as concerned in the final weeks in winning over the hearts and minds of the British public by means of a short, concentrated campaign of basic information and practical advice. Advertisements in the press and on television were accompanied by simple and direct posters, and the Board attempted to deliver a booklet to every household in the country. Though its arrangements were somewhat hampered by the inconvenience of a postal strike, no fewer than twenty million booklets were eventually distributed.

...quietly comes and goes

The Scotsman, 16 February 1971

D Day had long been set for Monday 15 February 1971. On the preceding Wednesday afternoon banks closed their doors to enable them to clear cheques and to balance and convert accounts; the Stock Exchange also closed; and on Friday it was the turn of Post Offices to cease business. On Sunday D Day was anticipated by British Railways and London Transport, and there was little doubt that the public could expect to wake up to a decimal Britain on Monday morning.

And so it proved, with an immediate and massive switch to decimal trading. The public was assisted by the prominent display of old and new prices and the larger department stores had specially trained members of staff available to offer assistance to anyone confused by the change. But D Day went so well that the next day it was not even the main story in many of the national newspapers. The only discordant note was struck by criticism of the small size of the ½p and the fear that traders had taken the opportunity to increase prices.

Little more than a week after D Day the United Kingdom was for practical purposes a decimal country. For the moment old pennies and threepenny bits could still be used but so successful was the change that within a couple of weeks they had all but disappeared. Indeed, the transitional period was brought to an end on 31 August 1971, months ahead of schedule, and it was possible to enquire, as many did, what all the fuss had been about.

That such a question could be asked was an unspoken, but deserved, acknowledgement of a quiet revolution brilliantly accomplished.

Take the virtual tour

You might also like

Pounds, Shillings and Pence

The pre-decimal currency system consisted of a pound of 20 shillings or 240 pence.

The Move to South Wales

In 1966 the decision to adopt a decimal currency system, required the Mint to strike millions of decimal coins.

The Royal Mint Advisory Committee

The Committee was established in 1922 with the personal approval of George V.