First coins of the Irish Free State

By Barrie Renwick, FRCNA, FCNRS

A country’s flag, its postage stamps and its coins are the symbols that represent a country to the world. When the Irish Free State emerged from British rule in 1922, to self rule like a Dominion, these symbols were needed for the country’s image. Internal talks were held, ideas debated and gradually decisions on these matters came forward.

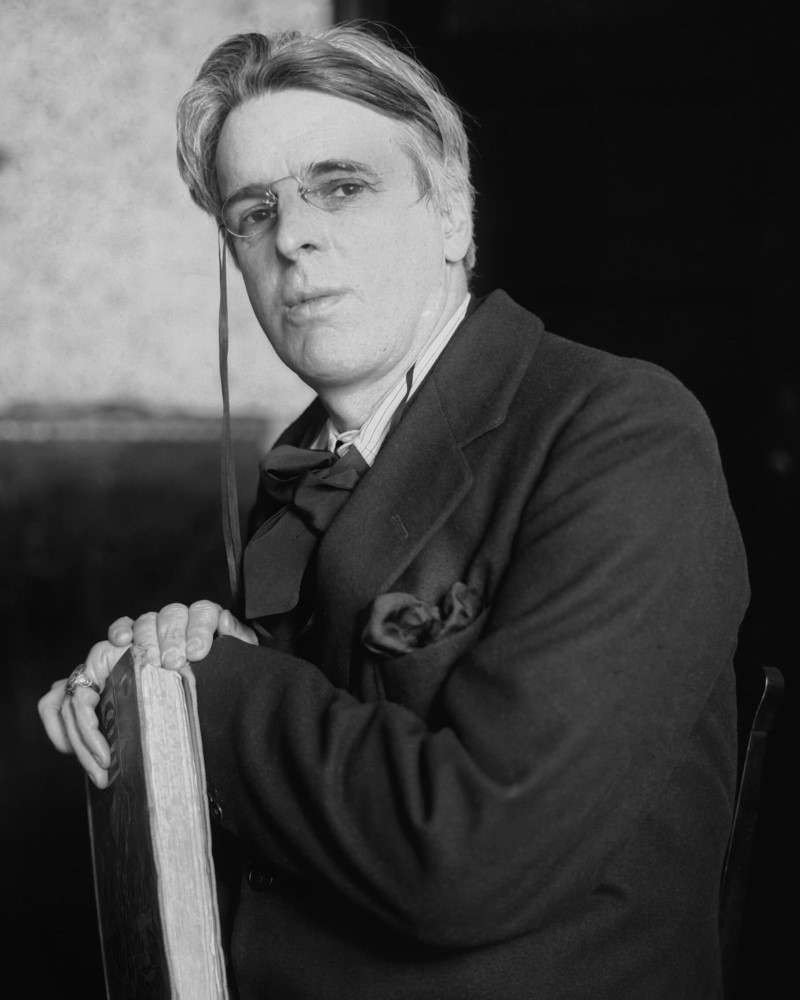

In 1926 Ireland’s Dáil Éireann, its government, created a Coinage Committee of five with poet W.B. Yeats as chairman. Yeats was told his committee should seek designs for new Irish coins, in the customary denominations, so that the country’s British coins could be replaced. Self-interest factions clamoured for their own design choices: Lobbyists in the dominant Catholic Church and its laity demanded ecclesiastic images, including saints. Northern Ireland’s citizens, who would also use these coins, pleaded that coins keep the portrait of the king. The new government frowned on these ideas and in their directions to Yeats cautioned that his committee pick solutions allied to the ethos of all Irish.

First discussions in Committee quickly agreed that the Irish harp epitomized Ireland, so the harp’s image would stand alone on the obverse of its coinage. That was settled. Next: Ireland had long been an agrarian society dependent on husbandry, thus depictions of indigenous and domestic animals on coins’ reverses would support that heritage. With these decisions, the Committee advanced, inviting a few noted artists to submit coin designs for consideration. Together with the invitation, the Committee included some pictures of classic animal-type ancient Greek coins, to illustrate how Ireland’s coins might reflect. Seven artists competed; three were Irish, two of the seven were medallists.

The animal-theme coin designs, sixty-six in all received, were judged anonymously and separately in February 1927. Each judge chose eight reverse designs; all picked the designs of English medallist Percy Metcalfe. As well, they chose his “Brian Boru” Trinity College harp obverse with its legend Saorstat Eireann (Irish Free State). Metcalfe, cannily sensing his reverse designs might attract as a group, had included an extra animal reverse, an alternative should another get rejected. This one, a ram, stayed unused. The Committee ranked those chosen from the noblest animal to the humblest, the way they’d appear on coins of descending value: the Hunter horse, 2/6; the salmon, 2/-; the bull, 1/-; the wolfhound, 6p; the hare, 3p; the hen, 1p; the pig, ½p; and the woodcock, ¼p. The domestic animals relate to husbandry; the others to hunting.

When news of the new coin designs broke in public, there was strident abuse from those opposed and raucous glee from supporters but little complaint from any votary about absence of the king’s image. In time objectors yielded grudgingly to the concept of animals; still it was the choice of the pig that they hated. They railed that it was dirty and was often ridiculed by others in cartoons showing Paddy and his pig. The agronomists extolled the pig as being familiar to every farm and vital to Ireland’s food resource. As concerns waned, some criticisms devolved into picayune grumbling about the unrealistic physical shape of the pig and of two other animals, something Metcalfe quickly amended. What emerged as new coinage outshone the fusty pocket change in use. And when the new money arrived in hand in 1928, it and its aura of Irishness overshadowed the irony that these were coins designed by an Englishman, denominated in the English way, and made at the English mint. The Barnyard Collection’s popularity at home and abroad soared, and remarkably, four of its reverse designs have endured for nine decades. And the obverse harp’s image continues too; it also continues in the Seal of Ireland. Éirinn go Brách.

To find out more about the development of the Irish Free State coinage watch the short film below from Screen Ireland

You might also like

Percy Metcalfe

Percy Metcalfe’s distinctive art deco style seems strikingly modern in the context of other artists working for the Royal Mint at the same time.

A stamp of Royalty

Find out how the life and service of Her Late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II was marked in stamps.