Coronation

By Sir David Cannadine FBA FRSL FSA FRHistS FRSA

The Coronation of King Charles III on 6 May 2023 will be a first-time experience for most people, as it takes place almost exactly seventy years since his mother was crowned in Westminster Abbey on 2 June 1953, which means that only a small minority of those who were alive then are still here to make comparisons between the two ceremonies. On that far-off June day, Queen Elizabeth II was a mere twenty-five years old, and with her Silver, Golden, Diamond and Platinum Jubilees stretching out before her, she became our longest-reigning monarch. This, in turn, means the gap separating King Charles III’s coronation from his mother’s is the biggest in our nation’s history, and his crowning will surely inaugurate a new sequence of coronations that will be much closer together.

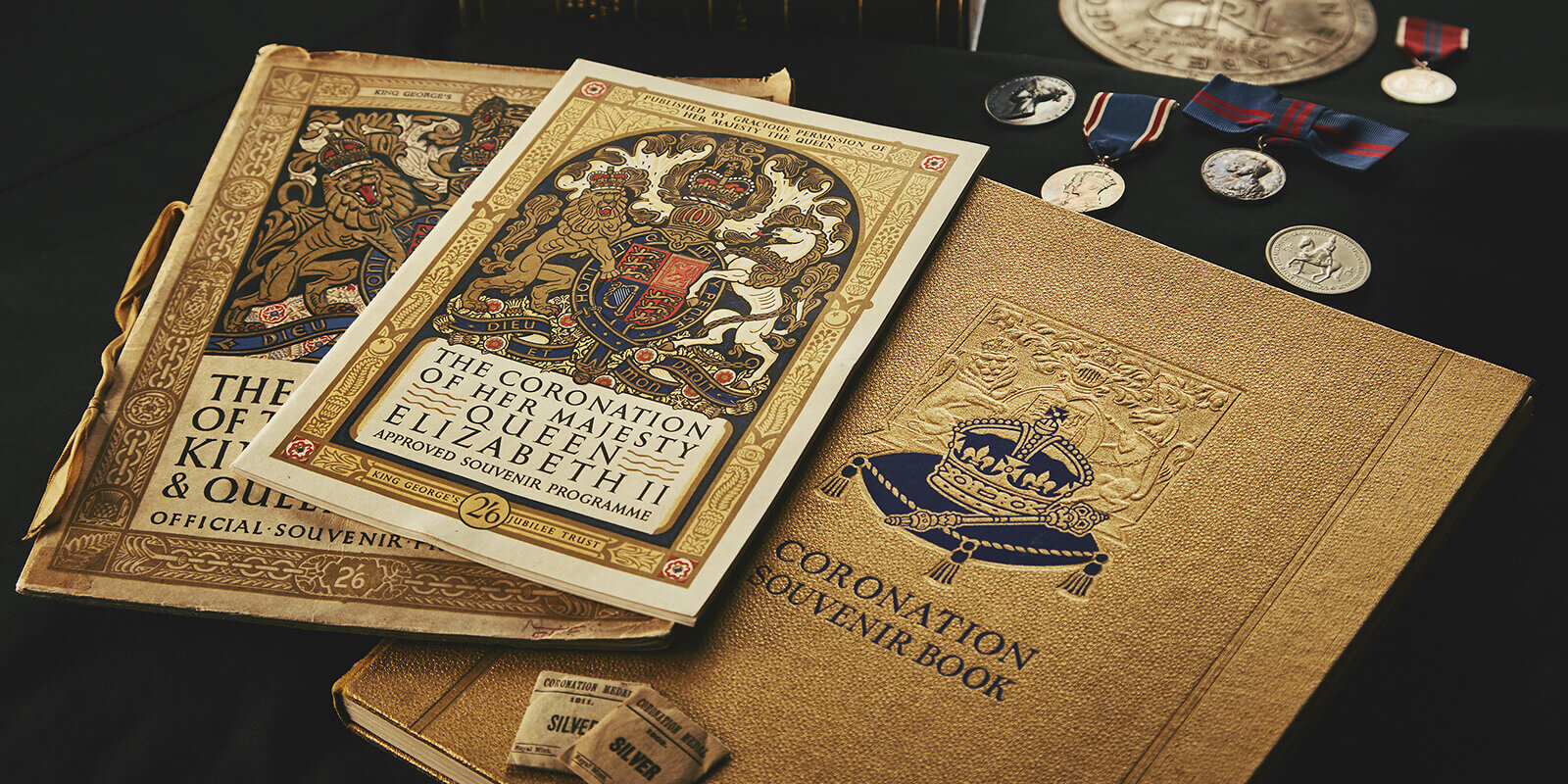

Like many aspects of the British monarchy, there are precedents for that. During the first half of the twentieth century, Queen Victoria’s long tenure of the throne was followed by four much shorter reigns and thus by more frequent coronations: King Edward VII’s in 1902, King George V’s in 1911 (there was no coronation for King Edward VIII), and King George VI’s in 1937 -- a rapid sequence brought to an end with the crowning of Queen Elizabeth II fifteen years later. As a result, many people who watched her coronation on television, or listened to it broadcast on the wireless, would have lived through this whole sequence of the four crownings that had taken place across little more than fifty years.

These coronations were not only linked together by their relative closeness to each other compared to what had gone before and as distinct from what was to come after, for in addition, they were all, by intention and design, imperial events as well as national occasions. Following the precedent set at Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897, troops from all parts of the British Empire paraded and processed on the streets of London, the dominions of Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa were strongly represented in Westminster Abbey, and also present were monarchs and emirs and sultans from the crown colonies, most memorably the Queen of Tonga. There were also lavish festivities held around the Empire, from Sydney to Singapore, Lagos to Toronto, Cape Town to Nairobi.

To be sure, India had gained its independence in 1947, but the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II five years later remained an essentially imperial occasion. Winston Churchill was back in 10 Downing Street, a British-led expedition conquered Mount Everest in a late imperial adventure, and the young queen declared her faith in Britain’s future global greatness – a hope that was brutally undermined by the Suez fiasco only four years later. Thereafter, what remained of the British Empire was rapidly dissolved, and most of it had gone by the mid 1960s. Internationally, the dominant theme of the reign of Queen Elizabeth II was great-power downsizing and imperial recession, although she herself never admitted that was what was happening, and she remained strongly committed to the idea and the ideal of the Commonwealth. Being head of that organization also gave her a role on the world stage that she shared with no other sovereign, which was underpinned and reinforced by her extraordinary longevity.

By contrast, it seems entirely right that the coronation of King Charles III should be a much less grandiose affair than those of his mother and her immediate sovereign forebears, with fewer guests invited to be present in Westminster Abbey, reduced contingents of British and Commonwealth troops on parade, and a more limited processional route through the streets of London. And this realistic accommodation to Britain’s diminished status in the world will surely set the precedent for the crownings of King William V and King George VII that are scheduled follow. All this is but another way of saying that, across the centuries, the coronations that have taken place, initially in England, and subsequently in the United Kingdom, have shown a constantly shifting balance between continuity and change, tradition and innovation.

At different times, they have been well performed, indifferently staged, and even downright chaotic. They have been English occasions, British occasions, and imperial occasions. Most of the current regalia, which Shakespeare described in Henry V as ‘the sceptre and the ball, the sword, the mace, the crown imperial,’ dates from significantly after his time. And the Coronation oath, which abjures the sovereign to uphold ‘the Protestant religion by law established’, was only inserted in 1688 to rule out the possibility of a Catholic monarch, and seems out of place in our contemporary, multi-faith society. On the other hand, there are many significant continuities in the coronation service: the anointing of the sovereign with holy oil, the presentation of the regalia, the crowning and the homage. And coronations at Westminster Abbey date back to 1066, while the chair on which King Charles III will sit has been used since late medieval times.

Image copyright: Dean and Chapter of Westminster Westminster Abbey

Before the First World War, most of the greater and lesser European monarchies staged coronations that became increasingly elaborate from the 1880s onwards: thus understood, Britain was merely one competing ceremonial cynosure among many. But the First World War witnessed the end of the other three great power, imperial dynasties, namely Czarist Russia, Wilhelmine Germany and Austria- Hungary, and coronations also went out of fashion among the other, lesser continental monarchies that survived. In recent times, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands and Spain have all turned away from such grand ceremonial inaugurations of new reigns, which means that the British monarchy is now unique and alone in continuing with coronations: ‘the tide of pomp’, as Shakespeare put it, ‘that beats upon the high shore of this world.’