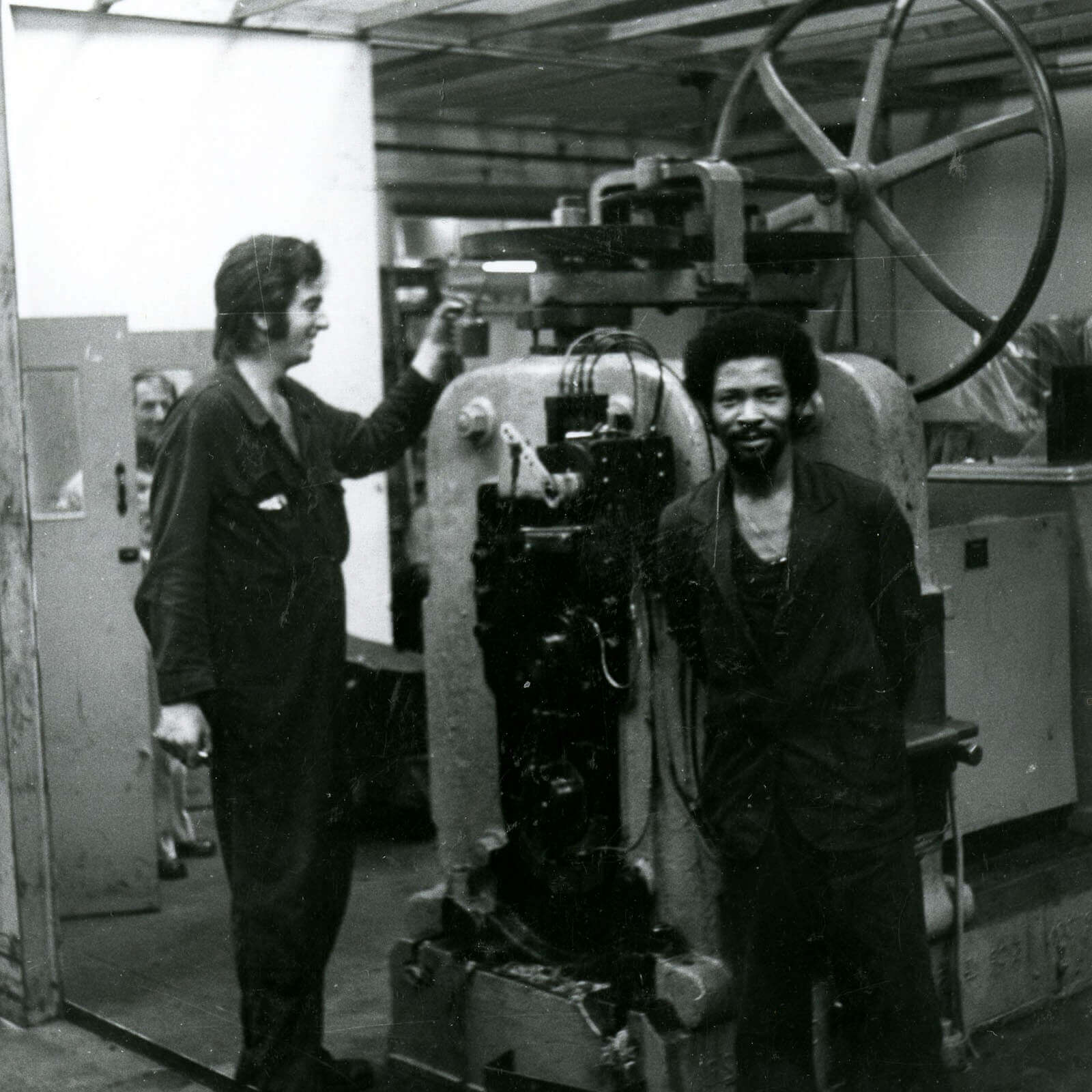

Workers at Tower Hill

The workforce at the Royal Mint during the 1940s – 1960s was as diverse as the Tower Hill area surrounding it. Many people who had immigrated to the United Kingdom during this period, some as part of the Windrush Generation, found plentiful work available in industrial and administrative roles.

Visit of Queen Elizabeth II to the Royal Mint at Tower Hill, 1966

By June 1965, a total of 32% of the workforce in the Operative Departments and the R&D Departments was comprised of employees who had immigrated to Britain. Of the 650 total employees in these departments, 147 had travelled from the West Indies, many of whom would have been part of the Windrush Generation, who arrived in the decades following the Empire Windrush’s voyage to Britain in 1948. The influx of a workforce from around the world brought together a mixture of cultures, and unfortunately led to an increase in instances of racial discrimination across all parts of life.

In 1951, a letter was submitted from the National Union of Students (NUS) Department of Vacation work to the Parliamentary figures who were investigating allegations of a ‘colour bar’ operating among some government departments and unions, among which the Royal Mint was mentioned. A ‘colour bar’ is a system in which black and other non-white people are denied access to the same rights and opportunities as white people, and the opportunities in this context were temporary work placements that might help students gain vital experience of the workplace.

Members of staff at Tower Hill c.1960

The Royal Mint at this time frequently called upon local labour exchanges to fill vacant posts, such as the Stepney Labour Exchange, and the letter alleged that the NUS had been contacted by the Labour Exchange for student workers, but that “the students might be in a position of authority and that they should not be coloured students”. Such a stance would have constituted a colour bar, though it was in fact an issue of miscommunication. The Royal Mint had placed a request, six months prior, for Temporary Supervising Officers, a position requiring a specific skillset and qualification. The NUS response to the Labour Exchange’s request for student workers was, quite fairly, that they could provide candidates on the condition that a proportion of non-white candidates were appointed. As the Deputy Master of the Royal Mint, Lionel Thompson, clarified in a subsequent letter, this request was not one the Royal Mint could accept, owing to the need to thoroughly vet all candidates for such positions:

“Our security organisation at the Royal Mint depends for its effectiveness upon the personality of the Supervising Officers; we must therefore, pick the best candidates out of any batch put forward.”

He added also that he did not feel it useful to have approached the NUS at all in this instance, because “one would not generally look to a body of students for people with this particular type of qualification”.

Though the allegations of any kind of colour bar were not deemed credible enough for serious media attention, and likely the result of miscommunication, the prejudices they hint at were not unheard of, and may well have been felt more keenly at the Royal Mint than in other Government departments in the 1960s. The Mint’s location, and its need for labour employment alongside administrative employment, meant it drew from the surrounding Tower Hamlets area for recruitment:

“…the Mint’s catchment area for industrial staff recruitment is the very difficult central London area, and in present circumstances, the vast majority of applicants for unskilled and semi-skilled employment are coloured men. As a result the number of successful applicants contains a high proportion of coloured men”.

Outing to Margate, June 1967. Hormer, Wally, Mitchell and Horace

Changing demographics in the Mint’s employment led to what reports and letters from the 1960s describe as “increasing evidence of friction between black and white elements”. This friction was heightened by the hierarchical structures present in industrial employment; complaints were sometimes raised resisting the appointment of black men to supervisory positions, or on occasion alleging that white supervisory staff were more lenient with non-white men for fear of being accused of prejudice. Some members of the workforce raised general complaints about cultural differences, such as eating habits in the canteen, and working or social habits during work hours, but reports generally conclude “there has not been firm evidence to show that [the behaviours of] coloured staff are worse than elements of white staff”, and that many complaints ultimately resulted from an overcrowding of staff following expansion of the workforce. As one report concludes, “although coloured men are not solely responsible for abuses, they are inevitably blamed”.

The changing demographics of the Royal Mint evidently proved a new experience and challenge for some of the established workforce, but one that soon proved to be a positive one. A letter to the Home Office of 1966 discusses the challenges of ensuring the workforce got along, along with the steps toward solutions. Different toilet types were installed in the factory areas, to suit the requirements of all staff, and the ‘antiquated and over-crowded’ facilities for resting were refreshed and expanded to avoid minor grievances turning into major points of friction. Specific new instructions were also given to foremen, codifying many of the rules in place and ensuring a common standard of treatment for all workers.