James II

Summary

The brief reign of James II saw few major changes in the denominations or designs of Britain's coins from those of his predecessor, Charles II. Silver designs were simplified, and denominations that had found their shape and style in the previous reign were solidified. The recent advent of mechanised coinage production in England meant that the reign of James II was the first in which exclusively milled coins were struck, rather than hammered coins or a combination thereof.

Mint and mechanisation

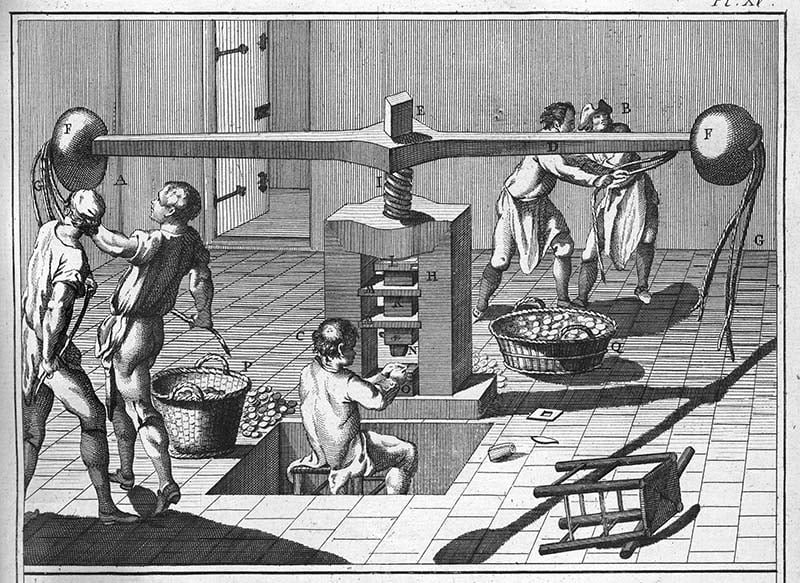

The preceding reign of Charles II had seen considerable mechanisation and modernisation of minting equipment, resulting in much of his coinage being milled rather than hammered. Even so, the reign of James II is technically the first in which an exclusively milled coinage was struck, marking the absolute transition away from early hammered coins. Milled coins struck in this way were produced via machinery such as the screw press pictured below, and while production was considerably faster – a coin every two seconds or so via the screw press – it was still just as, if not more so, labour intensive as hand-striking hammered coins. This process is not new to the reign of James II, and more information can be found on our pages relating to Charles II.

17th century French engraving of a screw press.

Royal African Company

James II is intimately connected to the Royal African Company (RAC), and the movement of gold and enslaved people from West Africa – to an even greater extent than his predecessor, Charles II. Charles II established the Royal Adventurers into Africa (later the Royal African Company, or RAC) in 1660, though it was James II, then the Duke of York, who served as its Governor. This was a position retained by James throughout the existence of the RAC in the reign of Charles II, and through the entirety of his own reign until his deposition.

In 1672, the RAC began militarising more heavily in continued pursuit of African gold and silver, and in the new pursuit of enslaved people. By the 1680s, the RAC was transporting thousands of enslaved people a year – some of whom were branded as the property of RAC or, specifically James II, then the Duke of York – and the RAC would go on to become the most prolific slave trading institution of the triangle trade period. Throughout this period, the RAC also fulfilled its original brief of supplying gold from West Africa to produce the gold coins which were, by this point, known as Guineas and the Guinea family. The elephant or elephant and castle sometimes found on these gold coins is the symbol of the RAC.

Gold coinage

The gold coins of James II’s reign are of the same denominations as those of Charles II, and they largely resemble them in type and design. The guinea family consists of a large five guinea piece, the two-guinea, the guinea, and the half-guinea, each sharing the same reverse design of four crowned shields with two sceptres intersecting them in a cross. Following the introduction of the guinea in 1663, these gold coins began to take on an increasingly visible role in commerce and industry, with bankers basing their reserves on them. The latter third of the seventeenth century, including the reign of James II, saw a healthy demand for gold, and while the coin officially circulated at 20 shillings its exchange value, and the value of the precious metal itself, began to rise beyond that.

James II guinea family. Five guinea piece (RMM747), two guinea piece (RMM748), guinea (RMM750), half-guinea (RMM752)

The gold used to strike guineas was sourced from the Guinea coast of Africa, largely by the Royal African Company (RAC), whose mark is sometimes seen on the gold coins in the form of an elephant or an elephant and castle below the bust. The five guinea piece still features the edge inscription of DECVS ET TVTAMEN (an ornament and a safeguard), which would later be reused on the £1 coin introduced in 1983.

James II guinea (RMM749)

Silver coinage

Silver coins struck during the reign of James II were of the same denominational structure to that of Charles II, and feature all of the expected denominations from crown to silver pennies, including Maundy money.

Though the reverse designs of James II did not change greatly from those of Charles II, some changes are visible on the silver reverses. The larger silver denominations of crown, halfcrown, shilling, and sixpence all feature plain fields between the shields, whereas those of Charles II featured in each of these spaces a pair of interlinked ‘C’s. The only provenance mark to appear on the silver coinage is the Welsh plume, which is found very rarely on some shillings.

James II crown (RMM755)

Charles II crown (RMM650)

Changes are visible also in the smaller silver, including that of Maundy money: whereas that of Charles II had featured large and interlinked ‘C’s on the reverse of the penny, twopence, threepence, and fourpence, those of James II feature instead large, crowned roman numerals: I, II, III, and IIII.

James II fourpence (RMM769)

Tin coinage

The base metal coins of James II are exclusively tin, rather than copper, and consist of a halfpenny and a farthing. Each of these pieces features a seated Britannia on the reverse, and the matching inscription of BRITANNIA. The obverse includes a shorter inscription than that of the precious metal coinage: JACOBVS SECVNDVS (James II). James II faces in the opposite direction on the tin halfpennies and farthings to that of the precious metal coinage, as was the case with Charles II, and there are three main bust varieties in the portrait. The halfpenny features a laurel and draped bust, and the farthing features primarily a cuirassed bust, with some draped bust varieties dated 1687.

Gun money

After his deposition in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, James II fled to France before, in 1689, sailing to Ireland in an attempt to raise and army and recapture the English throne with a Jacobite army of French and Irish soldiers. He was well-funded with gold crowns, courtesy of the French king Louis XIV, but the scale of the war, the size of the Jacobite army, and the poor infrastructure of tax collection in Ireland required of James a considerable extra sum to fund the campaign. The solution came in the form of ‘Gun Money’: base metal coins to be issued as promissory tokens, which could be exchanged for silver counterparts upon James’s assumed victory.

Gun Money was struck in a range of base metals, including copper, tin, and pewter. There are a great many complicated types, as in most cases the dies were changed monthly and dated, to allow for the expected repayment in silver to take place gradually and by date on which the base metal piece had been issued. The metal used for striking was often salvaged, ostensibly from guns, but also from all manner of metal objects including church bells. Gun Money was initially produced in Dublin, but a mint was also set up in Limerick to meet demands.

James’s Irish campaign was ultimately unsuccessful, and the Gun Money was thus never repaid. It continued to circulate in Ireland – at a reduced value – for around a century thereafter.

James II shilling (RMM5522)

Engravers

Die engraving during the brief reign of James II continued to be the work of Chief Engraver of the Royal Mint, John Roettier (1631-1700). The three Roettier brothers, John, Joseph, and Phillip, had been invited to England at the request of Charles II, who had come to know and trust them during his time in exile. John Roettier also produced the coronation medal for James II.

James II coronation medal

Engraving for the original punches and dies used for Gun Money, following James’s deposition, was also likely the work of the Roettier family: alongside John Roettier at the Royal Mint were his two sons, James and Norbert, and John’s brother, Joseph, was the Engraver-General at the Monnaie de Paris. The family was well-associated with the Jacobite cause both before and after the Irish campaign, and John Roettier was responsible for the piece punches and dies of the earlier James II coinage, from which a portrait could be taken.