The Value of Small Change

1908 Circulated aluminium East African one cent coin in a corroded state

To date, we have catalogued over 17,500 overseas coins. Many of them are large and impressive but, as we have discovered, it is important not to overlook even small coins in poor condition as they can also tell a fascinating story. Recently we came across an intriguing collection of aluminium one cent coins from East Africa, dated 1908. They are light weight with a perforated centre and some of them are covered in a thick powdery white corrosion layer. These aluminium coins are the first of their kind produced by the Royal Mint and, although they appear to have little value, they represent adaptability, innovative science and a commitment to continuous improvement that had gained pace when Charles Fremantle was Deputy Master of the Royal Mint (1868-1894).

Introduction and Design

To investigate the story of the aluminium coins we referred first to the Royal Mint’s annual reports, housed in the Museum’s extensive library. We discovered that in 1905 steps were taken to introduce a series of new coins into parts of both East and West Africa. The reports from this time specifically state that the lowest denominations should be made of a metal ‘other than British bronze, which might be acceptable to the natives and conveniently adapted to their requirements'. It was ultimately determined to use aluminium to produce the East African one cent coin and the West African one tenth penny. They were both approved for production in 1906.

The Royal Mint’s annual reports in the Museum’s library

For practical reasons aluminium was deemed an appropriate choice to manufacture these low value coins. It was a cheap material and, in the Daily Mail in 1908, William Ellison-Macartney, Deputy Master of the Mint, explains that this extremely light metal was needed due to the volume of coins required. He also suggests in a quote from the Los Angeles Herald, in March 1908, that ‘it is the best non-germ bearing metal known’.

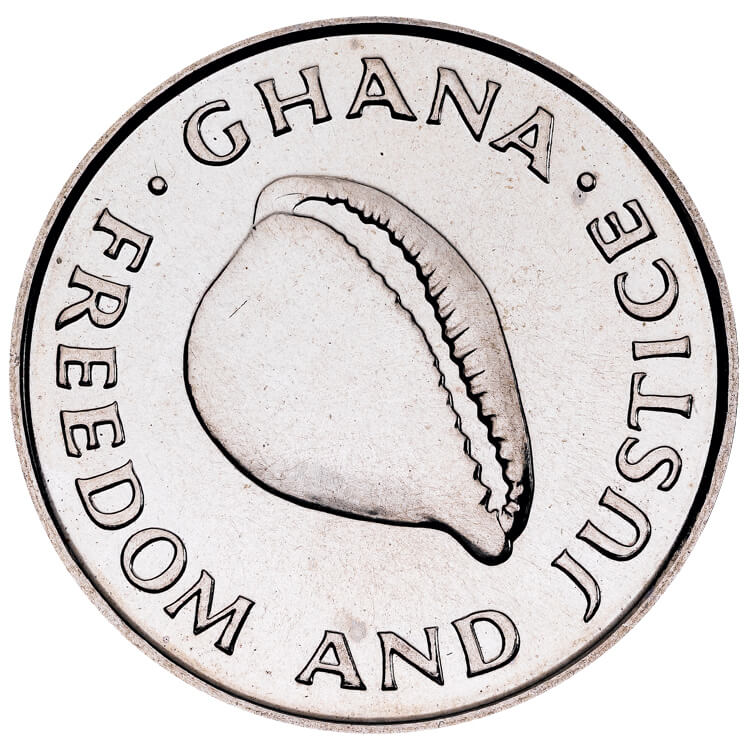

The central perforation in the coins was designed to allow the African people to string them together, the traditional method of storing the cowrie shells which were used as currency in both East and West Africa.

Cowrie shells similar to those used as currency in parts of Africa:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cowry_money_Monetaria_annulus_1.JPG

It was hoped that this design feature would encourage people to adopt the new fixed value aluminium coins which ‘ought to be of great advantage to the general trade of the country’. It is interesting to note that colonial Europeans believed people would have difficulty understanding new currency when in fact traditional African currency was far more complex than the European money. Today the cowrie shell is still memorialised on the Ghanaian 20 cedis coin.

Ghanaian 20 cedis coin

Production

The introduction of aluminium presented difficulties for production. The manufacture of perforated coins usually required specially designed presses and in nearly every case they had an unpleasant burr around the central hole. A report from the factory does not go into detail about how these problems were solved but, following a series of experiments, three of the cutting presses were adapted and one small press purchased for cutting the aluminium blanks. Two further presses were manufactured by Messrs Greenwood and Batley, and together the six presses were sufficient to supply all the blanks required for the coinage. Special care was taken with the designs of the coins to adapt them for the work and a method was found to enable the coins to be struck at a rate of 110 per minute. As an added benefit the aluminium used was so soft in comparison with bronze that the dies lasted much longer than usual.

Punches and dies for East African coinage 1906-1908

Problems with the Coins

Production of the coins continued for the next two years but by 1909 reports were being received that the aluminium tenth-pennies from West Africa were becoming swollen and then crumbling away. Soon the composition of the both these and the East African one cent coins had been changed from aluminium to cupro-nickel. The coins were struck in a similar size but were heavier in weight as a result.

Cupro-nickel one cent coins from East Africa, dated 1909

Annual reports mention the coins had been affected by the unsuitable climate, but after carrying out tests, the Royal Mint reached the conclusion that the damage was caused by salts from perspiration. Aluminium is highly stable in most environments but the presence of salts can cause rapid corrosion and it would seem that the combination of the coins’ composition and their storage close to the skin made it almost inevitable that they would be affected.

Despite the problems, a few generations later the Royal Mint was successfully using a new aluminium alloy. The alloy, which had to be purchased externally, contained less than 6% of additional elements such as copper, magnesium and iron but it prevented the catastrophic corrosion that occurred in the African coins.

Parallels

Parallels to this story can be drawn with the coinage for Jamaica in the 19th century. The bronze coins introduced into the British coinage in the 1860s were not suitable for the West Indies. The use of cupro-nickel had been considered during the trials for the British coinage by Thomas Graham, renowned chemist and Master of the Mint from 1855–1869, and Jamaica provided an opportunity to test the new alloy. The first coins in cupro-nickel were released for this purpose in Jamaica and, like aluminium, this metal has been a success for coinage all over the world.

Jamaican cupro-nickel penny dated 1869

You might also like

Fractional Farthings

Fractional farthings were struck in the 19th century but did not remain in circulation for long.

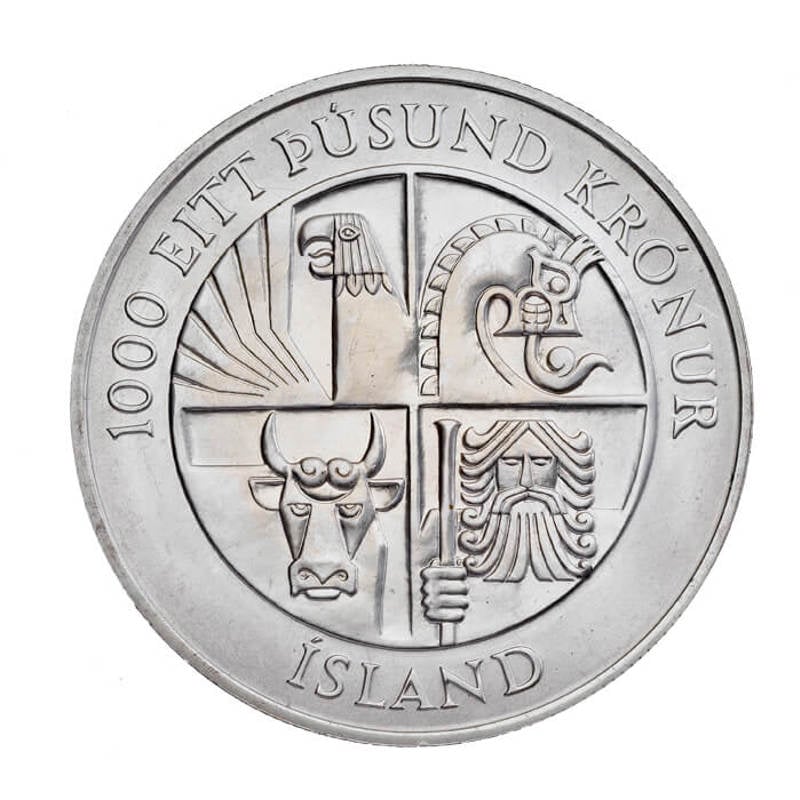

Coins of Iceland

The origins of Iceland’s relationship with the Royal Mint may be found in the Second World War.

Halfpenny and Farthing

Halfpennies and farthings become a regular feature of the currency in the 13th century.