Collection in Context

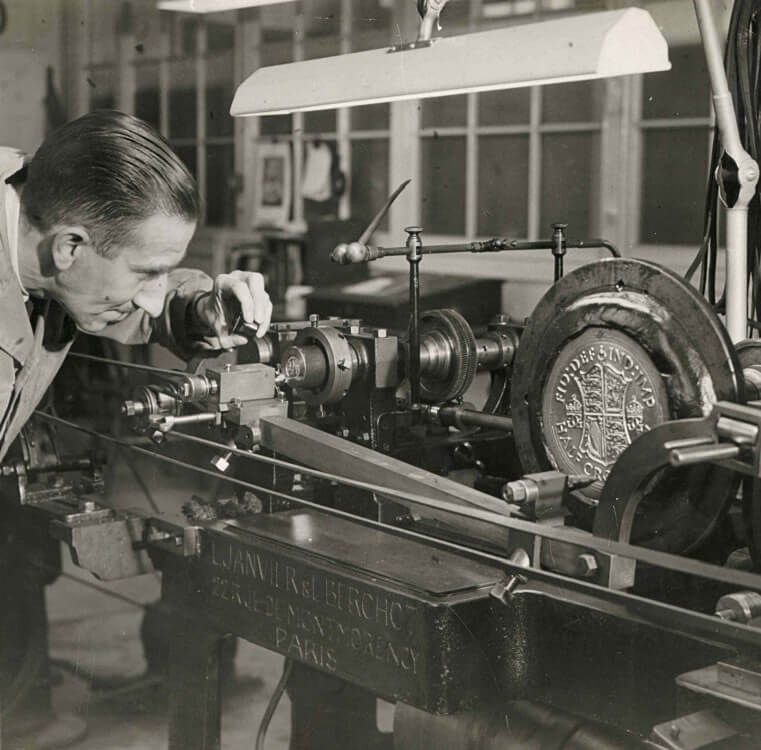

A Janvier reducing machine at work making a George VI half crown punch

If you have read previous blog posts about the Royal Mint Museum you will be familiar with the types of objects we care for, but you might not know how they were originally used. The plaster models, rubber moulds, electrotypes and punches in the Museum store each represent a stage in the process of transforming a design from a concept into a coin, medal or seal.

A design will usually start life as a drawing, selected in the case of UK coins by the Royal Mint Advisory Committee from a number of proposed ideas, though some artists prefer to submit their work in plaster or clay form. This design is then modelled in plaster to translate the drawing into a three dimensional work of art. Plaster is used at this stage because it gives a better finish than other materials used and allows any errors made to be corrected. Some artists today use CAD (computer aided design) modelling which, although requiring a similar degree of skill, can replace the method of working on plaster and results in an acrylic model.

Plaster model for the Mary Gillick coinage obverse of Her Late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

The plaster model is placed on a scanner where a digital camera photographs the details of the design from all angles. Modifications can then be made on screen. When finalised, the digital file is translated into a cutting programme, instructing a computer-controlled engraving machine to cut the design into a soft piece of steel at coin size, known as a reduction punch. This punch is the first in a series of tools which ultimately result in the finished dies used to strike the coins.

Tools for the obverse of a George V half crown (made in the era of the reducing machine)

The four stages of tooling pictured above enable the finishing touches to be made, working in relief then incuse then relief again. Any blemishes or flaws can be removed before the final die is made. If a die breaks or wears out in production, another can be made from the working punch.

To strike the blanks, the obverse and reverse dies are fixed in a coining press which, with modern machinery, applies a pressure of around 60 tonnes and turns them into coins at speeds of up to 850 a minute.

Before the development of the digital technology we use today, a silicon rubber mould would have been made from the plaster model. This mould was made electrically conductive and then electroplated with nickel and copper, yielding a reproduction in metal of the original model known as an electrotype.

Rubber mould and electrotype for the 1937 Irish Free State half crown coin

The electrotype was mounted on a reducing machine where its details were scanned by a tracer, working in the same way as a pantograph. The movements of the tracer were communicated to a rotating cutter which copied the electrotype at coin size into a steel reduction punch. The first reducing machine at the Royal Mint was bought by Benedetto Pistrucci in 1819 and these machines were used in production as late as the 1990s, first powered by pedal and then electricity.

Reducing machine tracing the electrotype for the 1895 India Medal

Before the introduction of a reducing machine, punches and dies were painstakingly created by hand. Some of the earliest punch tools we have in the collection are from the reign of Charles II.

Charles II portrait punch

It would take an engraver about a month of hard craftsmanship to make a tool such as the one pictured above.

Mechanisation in coin production was introduced shortly after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, in the form of rolling mills and screw presses, a huge step forward from the traditional hammering method used in the Middle Ages.

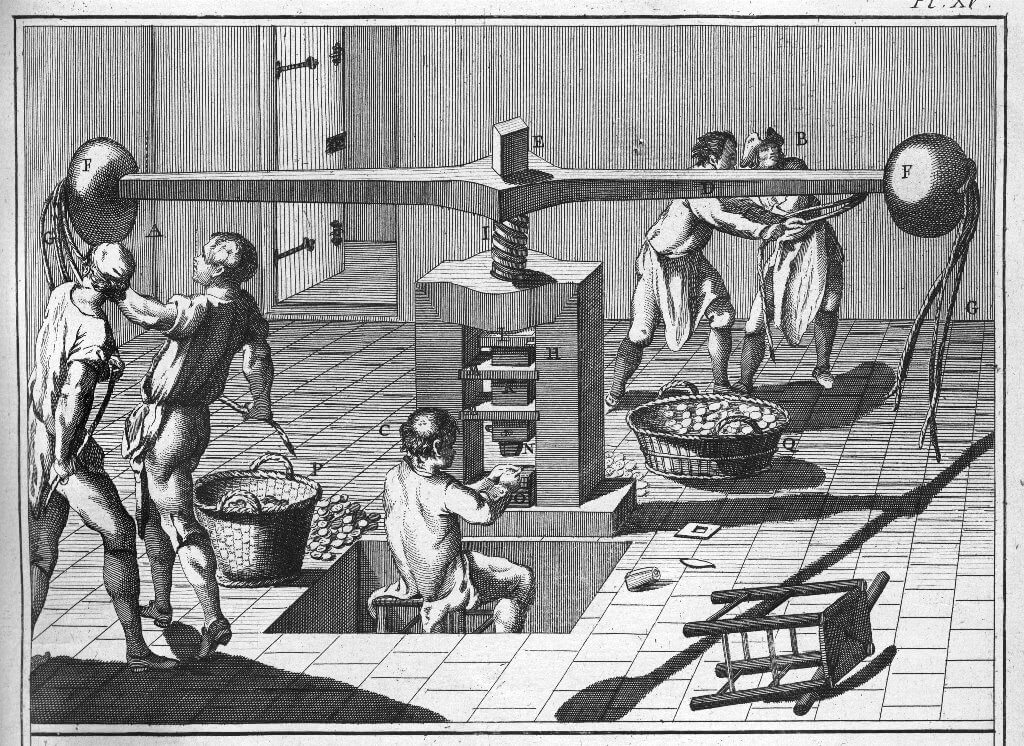

Engraving of a screw press at work

The screw press brought down the upper die onto the blank coin by the action of a large screw carrying the die in a holder mounted at its lower end. The screw was set in motion by workmen pulling at the weighted end of a long horizontal bar and descended with great force to hit the blank resting on the bottom die.

Essentially, the process in which a design makes it on to a blank coin or medal has not changed a great deal over time and this is evident from the Museum collection. The Royal Mint has adapted to new breakthroughs in technology to improve on long standing processes.

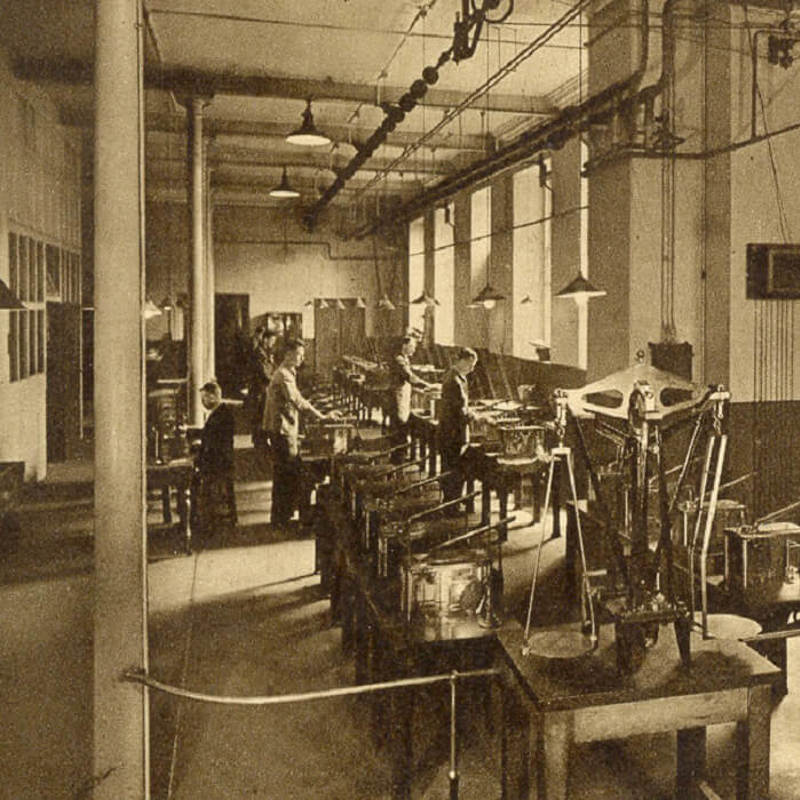

What has been described here is just an element of what the Royal Mint Museum holds. The collection also contains objects that tell the story of other important stages in the coin and medal making process, such as melting, rolling, blanking, weighing and counting.

You might also like

Janvier Reducing Machine

The Royal Mint's reducing machines were once vital tools in the coin making process.

Automatic Balance

The automatic balance reflects the Royal Mint’s dedication to precision and technical accuracy.

The Move to South Wales

In 1966 the decision to adopt a decimal currency system, required the Mint to strike millions of decimal coins.